And The Gods Play On

There is a home video of my Wayang Kulit teacher’s daughter playing with his puppets. She’s only three years old in the footage and her head barely reaches the bottom of the puppet screen. That doesn’t seem to bother her, though — sitting there at the base of the frame, she swoops one character up into the playing space with a quiet and determined focus. She moves its arm to touch another character’s face. She takes up the other character, too, and is soon pushing them together into an embrace that’s all the more endearing for its clumsiness. Her attention never strays from the puppets.

This is a girl who, now, a few years older, has become a perennial performer. She actively seeks out cameras, always wanting to show off the newest dance she’s picked up from youtube — and even more interested in subsequently watching herself in playback over and over again. Yet, in this video, as a little three year old, she never once turns to the camera. In fact, nothing about the video feels like an outright performance, at all — and why should it? This isn’t a puppet show for anyone but herself.

That was the only way he could capture the moment, my teacher interjects as we watch the footage one day. He begins to explain to me his frustrations surrounding the event: how, back then, his daughter would outright refuse whenever he asked her to perform for his friends; how she’d run away when he would ask again. If she’d known he was secretly filming her, she probably would have stopped then, too, he reasons. I tune my attention back to his daughter in the film. Now and again, I can barely make out her voice as it softly alternates between the two figures, creating dialogue and monologue, together. My daughter is fickle, my teacher mutters quietly.

I’m trying my best to recount this scene without over-sentimentalizing it, or, even worse, smothering it all together under too much “adult-speak." (Run, don’t walk, should you read the word “ludic" anywhere in this post.) Suffice it to say, the whole thing was beyond adorable — even as it was an all-together everyday moment. What little child hasn’t, at some point, played with their dolls or LEGOs or stuffed animals or miniature dinosaurs or pieces of fabric or a collection of sticks (and so on, and so on), bringing imaginative life to beloved toys and making everyday things a little more fun and personal? And what little child hasn’t done so in a way that was near exclusively intended for his or her own enjoyment? Entry into someone else’s imaginary (magical?) world is rare thing. Such places are expansive but fragile; you must tred lightly, careful not to break any rules you never knew existed — they do exist, they always do, and they’re integral to the reality of the place.

There was a while when I was younger — though older than three (and post Dog-and-Dog-and-Pillow days) — that my best friend and I got really into professional wrestling. Before we could get our hands on real action figures or any of the video games, we built three dimensional wrestling rings out of construction paper where we’d stage never-ending feuds between hand-made, cut-out paper figures. It was always too complicated to fight each other, so we’d take turns, each getting our own chance to play both characters, ring-side announcer, sound effect man, and crowd all at once. Watching this video of my teacher's daughter led me to think about those wrestling matches for the first time in years. I remembered how close I felt to that friend, how even with another person at my side, those matches were play, not performance. It makes me wonder whether that had had something to do with us being best friends.

When I return my focus to the video, though, it all suddenly feels different. Here was a three year old playing, but she's doing so with her father’s Wayang Kulit puppets, specifically. All-too-smooth universal associations aside, there are some undeniably specific cultural curiosities peppering this video. The skinny character with the elaborate headdress, for example, has his back arm positioned just right, so that its elbow carves a deliberately acute angle back towards its waist. And each puppet enters and exits in precise arcs, following trace forms that — I now know — are essential for casting expansive shadows upon their backdrop. And it's here that, as so often this year, something at once profound and obvious hits me: this is play and not performance, but it is also tradition. Sitting at her father’s screen, my teacher’s daughter was acting like any other little girl but also already training to become a dalang puppeteer.

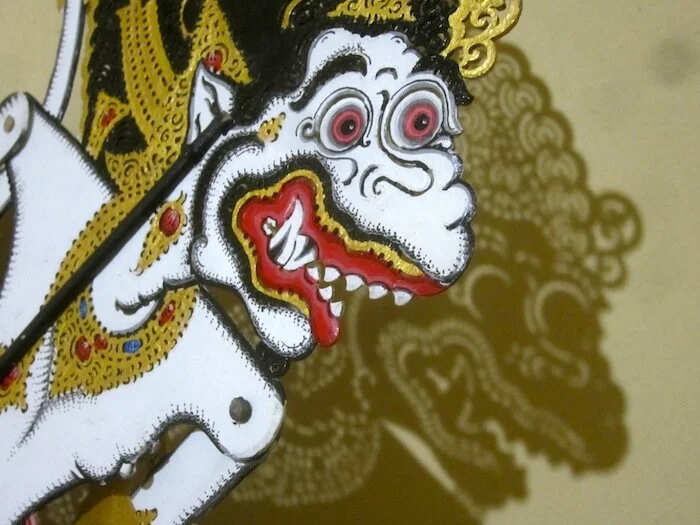

Of all the forms of puppetry I’ve learned this year, Balinese Wayang Kulit puppets are the simplest to individually manipulate. There really is something childlike in the way they move. Built from cow’s hide and manipulated from below, Wayang Kulit rarely have more than three points of individuated articulation. Each puppet is stabilized by a thick rod running up its middle. Some characters’ arms move on their own, with additional, thinner rods affixed to their hands that stretch down long enough for you to hold in yours, and the clown characters can move their mouths by pulling on a string running from the lower jaw to the base of the rod below. But — save a few special exceptions — that’s it. As dalang, you are the show’s only puppeteer. It is your job to bring these puppets, often as many as thirty or forty per show, to life. Should you need to control more than one puppet at once, you’ll usually be limited to a single hand per puppet, further reducing each character’s movement to a vocabulary of full body swings and turns and jumps and shakes. When two puppets fight, it’s not all that far removed from my days staging wrestling matches; figures fly around the playing space, full bodies collide, and only in special, intricate moments, will the more articulate arms come into play, with one puppet grabbing the other and tossing him about.

Artaud once described Balinese actors as animated hieroglyphs but the definition feels far more literally applicable for Wayang. These are figures forever confined to two-dimensions. Many characters feature designs that straddle front and profile views simultaneously— sideways heads and feet improbably cut by torsos turned directly towards their audience— but even these geometric twists are rendered flat on the cow’s hide and by the shadows they cast.

For all their limitations and lack of dimensions, though, Wayang Kulit puppets come to absolute life under the care of a skillful puppeteer. Their shapes speak words and their interplay makes sentences. Up on their screen, broad gestures gain new subtleties. A male puppet’s two arms dance around its waist until suddenly, with a swift diagonal motion, you realize that he’s tying his sash. Soon after, a clown character grows all the more arrogant and absurd through his continued attempts to turn his back on his comedic foil mid-conversation. I know this guy — you think as he moves from side to side, mouth furiously flapping to match the dalang’s snorting laugh. And then there are the shadows; each puppet is in constant collaboration with the fire hung less than a foot behind the screen. With nothing more than a quick shift of a puppet’s orientation to the flame, a single arrow can suddenly fire twenty times at rapid speeds by transforming back and forth from its realistic shape to a jetting streak of black. A worm can grow into a dragon by pulling the puppet closer to the flame, casting a larger, more terrifying figure on the screen. And even when a puppet remains still, its base rod affixed into material beneath the screen so it can remain onstage without being held by the dalang, its shadow continues to dance. As the flame moves, so does the puppet’s silhouette.

There is Arjuna, the crafty prince; Hanoman, the monkey king; Twalen, a lazy, overweight servant for protagonists; Delem, the boisterous, over-energetic aid to the antagonists— these are characters known by everyone who comes to see the show. Night after night these characters enact the same stories of princes and demons and animal lords locked in battle, tested by the gods, or spurned by love. Even as the plot varies from show to show, the super-structure remains the same. Protagonists enter from the dalang’s right, antagonists from the left. Love and seduction scenes come early, then travel scenes, then the big battles. The stories play out like animated comic books, fitting all the action within that familiar, rectangular frame, and supplanting all those explosive SMACK, POW, and THUD word bubbles with the percussive sounds of the cepalo, a wooden hammer clutched by two biggest toes on the dalang’s right foot that is rhythmically beat against the side of the puppet box throughout the show.

The use of this cepalo might help to hint at how much more than puppet manipulation a dalang must do. Beyond animating the puppets, during a performance the dalang must voice all the characters, speak in two to three languages, sing in ancient Kawi, relate all scenes and puppet movement to the accompanying Gamelan music, and join in the music by striking the cepalo. Get ready to improvise, too; not once have I seen an actual, written script, and local audiences aren’t too forgiving when they watch over-done gags or hear recycled material. Within the set format, clown characters may pop up whenever they so please, doling out tangential jokes, running vaudeville gags, even providing meta-commentary on the night’s offerings. These are some of my favorite moments in a Wayang Kulit show. The physical humor transcends language my barriers — though whatever they’re saying must be pretty good; I’ve seen audience members laugh so hard they’ve fallen out of their seats. During these moments, the dalang feels almost like a stand-up comedian, one who uses puppets to deliver his jokes from behind the screen (multiple dalang I’ve met work as bondres, masked clowns, as well). These bits can carry on for so long that you almost forget there is a plot, but then suddenly Bima, the warrior prince, comes crashing across the screen in a tussle with a large demon, and the story continues right where it left off.

As you watch Wayang, you’re not restricted to any one area of the performance space. If you’re tired of viewing the shadows, you can get up and walk behind the screen for a look at the dalang as he (or she, though usually he) conducts the evening’s adventure. Despite all the disjointed multitasking, the backstage atmosphere at a good Wayang peformance is strikingly calm. Assistants to the dalang prepare the next puppets for their entrance and tend to the flame while the dalang bounces from character to character, swinging his voice from high and nasally to deep and guttural with astounding ease. It’s easy to run things at a frenetic pace, but the best dalangs can always turn at a moment’s notice, throwing puppets around before stopping all at once to deliver a punchline.

But even watching from behind the screen cannot offer a complete picture of the dalang’s role; though a puppeteer, a dalang is equal parts shaman and priest, as well. He is a conduit of the cosmos. He begins every show with prayers to the Gods, seeking permission and assistance in the task of replicating their roles in miniature. The white screen that houses the night’s shadows mirrors the holy emptiness from which the world sprung — a fact acknowledged in a passage of ancient Kawi language that opens all traditional Wayang performances. It’s no coincidence that the vocal inflections and rhythmic patterns accompanying a dalang’s Kawi recitations sound so similar to the Kawi recitations heard at religious ceremonies, weddings, and offerings.

The dalang’s priestly and shamanistic duties come out in full when he is tasked with transforming normal water into tirta, holy water blessed by the gods and sought by ailing individuals who require purification. Following a special performance, specific puppets are positioned onscreen to create a holy tableau that will bear witness to the offerings and transformation. Flowers are placed in some of the puppets’ hands. The dalang performs a series of mantras and incantations while interacting with an elaborate system of offerings and religious instruments. Beginning with his puppet of the God Siva, the dalang stirs the tirta water with the base rods of the puppets in the tableau. Through the puppets, the gods reach the water. When the ritual is complete, the puppet screen is removed to reveal the intended recipients dutifully seated on the other side of the puppet frame. With tirta water in hand, the dalang blesses the recipients across this threshold at once literal and symbolic.

I was completely caught off-guard by the first purification ceremony I witnessed. Armed with a description similar to what I recounted in the previous paragraph, I assumed that the ceremony’s preceding puppet show would reflect the piety of the occasion with an appropriately austere performance. Instead, a massive demon soldier puppet suddenly appeared on the screen with a great spear in both hands and a penis twice as large. This other weapon had its own stick for manipulating and would rise and fall in coordination with the demon’s high pitched cough. For the next fifteen minutes, I watched in hilarious disbelief as one of the clown characters — who, up until now, had been head-butting his enemies in the crotch — tried to figure out how to defeat his most formidable opponent yet. The audience ate it up. Forty-five minutes later, they sat respectfully quiet as the holy water was blessed.

It’s experiences like these that leave me feeling like I’m always at least one step behind whatever’s happening in Wayang Kulit. That’s not at all a bad thing— I should add— and it’s hardly surprising; Wayang Kulit is thought to be the oldest form of puppetry in all of Asia — centuries of culture and tradition have been distilled into these two-dimensional figures made of cow’s hide, black leather sealer, and acrylic colors. To study Wayang Kulit is to be thrown right into the middle of it all, and even more so if you’re entering its surrounding culture for the first time.

In the days leading up to my first performance, I felt particularly overwhelmed by all that I was stacking up against. There was just too much to learn— too many disparate skills to practice, too many languages to remember, too many cross-cultural peculiarities to bridge. I kept dwelling on something Jerzy Grotowski once wrote: A Westerner doing “Oriental" theatre is either "free" - and thus like a monkey imitating his master, making pseudo-signs without precision or usefulness, trying to find the “forces" manifested by actor/mediums, etc …. the affective imagination — or else he is a near-perfect Balinese, though not quite so good. Except, words twisted in my memory, all I could remember was that my two best options were to be a performing monkey or simply not as good as local.

At the top of the show, as the overture began, my timing was off on a few of my first cepalo strikes. I winced. Already, I was making a mess of things.

But the show went on, no problem. When you get down to it, it’s really just me and puppets back there — so long as I didn’t stop, no one else could. By the end of the opening scene I had loosened up. Jokes came easily, sudden improvisations surprised even me, and people laughed. This wasn’t so different than my paper cut-out wrestling matches, after all— and “broad humor" is called so for a reason. By the end of the show, my right leg had gone numb from gripping the cepalo and striking the box. My voice was ragged. A few embers sat in my lap, loosened from the torch when a dragon puppet’s tail swung wildly at its eagle opponent. Never before had I sweat so much while sitting down. But I made it through, and it was pure fun.

There’s a whole lot about Wayang that plays out like that. Amidst the whirl of activities and sectioning of brain activity, you get to sit beneath the stars and tell stupid jokes that are somehow much funnier coming out of the mouths of puppet shadows. Characters speak in voices and sounds you stopped making when you turned fourteen and decided to “be mature" (next time you run into me, ask about the Wayang monkey voice). And when it’s all over, you’re just a guy again— most of your audience usually leaves as the show is wrapping, wisely recognizing that all the best parts have come and gone. It’s grounding, even as it’s fleeting, as exhilarating as exhausting.

Most of all, participating in a Wayang Kulit show — be you performer or audience —affords you the opportunity to share in an ancient tradition that is still thriving today. The performance culture surrounding Wayang Kulit feels equal parts respect for its own history and attention to little shifts in local life. Somewhere in every show you will find a quixotic collision of now and forever — a demon from the Mahabharata gets compared to Jet Li, or Siwa’s older brother meets a puppet with jerry-curl who speaks in gibberish skat and finishes every sentence with the word Jazzzzzz. Some things stay from night to night and century to century; others come and go, conceived by a dalang’s imagination but given life — or killed off — by the public. I think it’s this marriage of the longstanding and the one-time idiosyncratic that allows a three-year-old’s playtime and a holy ceremony to juxtapose so easily within the same evening. Everywhere you go, puppets are serious, religious figures. They hang on walls to invite good energy into a room. They have their own temples and holy days. They are to be treated with respect (whatever you do, don’t step directly over one). At the same time, they’re never treated with the kind of perverted preciousness many religious figurations receive in the West. These are mystical hieroglyphics, but dammit, if they want to fart on screen you can bet they will— and most people love them all the more for it.