Greetings! If you’ve found this page you’re quite the citation clicker! In 2011, I was named a Thomas J Watson Fellow, awarding me twelve months of international travel to engage in a topic of my own choosing. Through my project, Performing 'Model' Humans: What Puppets Can Teach Us About Empathy, I examined the relationship between puppets and people in a variety of performance cultures as a means for exploring ideas of imagination, projection, and empathy. I also kept a log of my discoveries, thoughts, travels, and adventures. You can read a curated ‘best of’ from that log below, in reverse chronological order.

To Go Home

I’m sitting on an airplane and I keep thinking about this short story called Kaspar Hauser Speaks. It’s written by an American author named Steven Millhauser and I first read it while riding the tube in London last fall. The thing’s a work of fiction, but it reads like it could have been real, written as if presenting the historical record of an important address given by the aforementioned Kaspar Hauser to the public of a town with a German name. “Distinguished guests,” it begins. “It is with no small measure of amazement that I stand before you today.”

It is possible that Kaspar Hauser is not entirely human. When he first arrived to this place, he was—by his own account— “a brutish creature, half idiot and half animal.” But he has made considerable progress since then. Through hard work and human help, Kaspar Hauser has quickly grown into the image of all those around him. “I am you—and you—and you” he says, “I who only a few short years ago was lower than any beast.”

Because of this, Kaspar Hauser’s human admirers think of him as a most impressive specimen. In the span of just three years his mental life has leapt forward an astonishing twenty. “I stand before you, a civilized man… a Wundermensch, as I have been called,” he notes. But to himself, Kaspar Hauser is trapped in limbo. While his friends and colleagues marvel at how far he has come, he feels only the unbridgeable distance left to travel. “Even the leap of which I speak, the tremendous leap toward you and away from me, a leap that leaves the bruise of my heels in my own sides,” he admits, “even this leap is no more than a sign of my difference.”

And so, for this publicized speech, Kaspar Hauser has invited the brave, the curious, the civilized, and the outraged to hear him answer the question they’ve all wondered since the first day they laid eyes on him: what is it like to be Kaspar Hauser?

To this, he offers his answer:

“To be Kaspar Hauser is to long, at every moment of your dubious existence, with every fiber of your questionable being, not to be Kaspar Hauser… My deepest wish is not to be an exception. My deepest wish is not to be a curiosity, an object of wonder. It is to be unremarkable. To become you— to sink into you— to merge with you until you cannot tell me from yourselves; to be uninteresting; to be nothing at all; to experience the ecstasy of mediocrity— is it so much to ask?”

I am not Kaspar Hauser. I will admit, however, to moments throughout my Watson when Kaspar Hauser and his speech rang loud and clear to me. A real high point of my year came in Japan when, communicating in only Japanese, I contacted and met up with an elderly maker of Karakuri— ancient Japanese automata. Sitting in his small workshop in an outer suburb of Osaka, I caught myself marveling at my own situation as much as I marveled at his ancient wind-up figures. Here I was cracking jokes and asking questions about the precursors to robots and the Bunraku puppet theatre in a language whose most basic characters had been nothing more than esoteric designs to me only a few years back.

It wasn’t twenty years mental progress in a span of three, but it was more than enough to make me feel like I’d arrived somehow. Within a world of unbridgeable gaps, it made for a good day.

But then there was the next day, and on that day I was back at the Japanese grocery store, my vocabulary nemesis, trying to determine the differences between containers of garlic sauce without having to ask an employee for help. Holding the two experiences side by side might make the second seem all the more trivial, but that’s sort of the point: even minor attempts to venture into foreign territory could all too easily lead me back to myself and to my own idiosyncratic traps and shortcomings. I believe in transformation— that’s what puppets do— but I found for myself this year that there is no such thing as reinvention or truly running away. There are only similarities and differences, gradients of change, measured from vague but oddly fixed points of origin.

It reminds me of a particular puppet featured in the last performance I worked on while in Melbourne, a human figure made of duct tape, who leapt through the air but froze in mid-stride to notice his own little duct tape limbs just before they all crumbled in on himself.

Puppets cannot save the world— if you’re inclined to believe in that kind of thing at all. They can make you laugh, they can frighten, they can tug at the strings of your deeply buried childhood wonder, and, if you’re lucky, they can even make you think, catch you off guard by how deeply they resonate after sneaking in through the back door.

Another figure with a German name once proposed the idea that a hammer is only a hammer to us when it breaks— only when an object ceases to fulfill its function will its user stop taking its existence for granted. Now, at the end of my year, I wonder how much further we can take this idea. Instead of breaking, what would happen if a hammer came to life? Or better yet, what would happen if two hammers came to life, one large and grouchy, the other small and optimistic? What if these hammers didn’t even know they were hammers? Imagine: an empty stage littered with old tools and suddenly two hammers rise up, look at one another, and begin to perform the opening scene of Aristophanes’ The Birds. Nothing about that scenario strikes me as inherently better or worse than a more expected, more physiologically human performance. True, most hammers are small and, so far as I know, all hammers lack the independent parts needed for dynamic movements or visible shifts in expression, but once this year, when I saw hammers perform, I was reminded of earlier, human performances I’d seen on nights when I could only afford cheap tickets and wound up sitting so far from the stage that I could barely make out the actors. What is so different between watching a human from two hundred feet away and a hammer up close? What if I replaced the hammer with a hand puppet?

I do not think these are trivial questions— not in an age when Tupac can return as a hologram to perform at Coachella and, in Japan, a fictional singer named Miku has been selling-out stadiums with her hologram shows for nearly half a decade. These are strange and brilliant times we live in. On the last day of my Watson, an unmanned, mechanical piano played Clair de Lune for me as I walked to my departure gate in the Melbourne Airport. It was unnerving.

I want to find a way to tackle these kinds of questions seriously without denying their beautiful absurdity, and I think puppet theatre can help.

Giving voices, faces, and even temporary souls to inanimate materials can de-familiarize the every day. It reminds us that just as we use things, we relate to them; that they gain lives because we can’t help but put ourselves into them. My mother still keeps the small pinecone she absent-mindedly held as she and my father walked around Walden Pond on their first, real date. She showed it to me once when I was sixteen and it was alive. I saw it breathe in time with her. It was puppet theatre before I knew what puppet theatre could be.

We in the Western world say animism, “but that simply places something primitive we can neatly file away and shelve, otherwise too troubling to look at,” writes Kenneth Gross. We flee from animism to thinking about the world only in terms of what things do and how they serve us— and technological advancements gainfully help us along. A puppeteer in Melbourne shook his head as he spoke about a child who stood in front of the refrigerator shouting “OPEN,” growing increasingly frustrated when the thing refused to do so. “Maybe our flight from animism is our flight from madness,” writes Gross, now quoting the playwright and puppet theorist, Dennis Silk. “We’re afraid of the life we’re meager enough to term inanimate. Meager because we can’t cope with those witnesses… if a cross is a witness, why not a loaf of bread, or a shoe-tree, or a sugar-tongs, or a piece of string?”

Or a person?— I would add.

At a puppetry conference in London last fall, I attended a panel discussion on directing puppet shows. At one point, the conversation turned to the question of what to look for when you’re unable to cast experienced puppeteers in your production. Consensus quickly settled on one main piece of advice: if you’re stuck with first-time puppeteers, it’s generally a good idea to seek out dancers before actors because most actors just don’t know what to do with a puppet. Actors want to make a puppet do what they want, the panelists agreed. Dancers are more willing to place themselves in service of the object.

I was struck by this conclusion in part because I remembered a similar conversation I’d once heard about good and bad acting. Good acting, some older, better actors told me, is always about the other person, while bad acting is about yourself. Good acting is truly listening to your scene partner, and then trying your very best to answer in turn. Bad acting is admiring your own performance and ignoring everything else. It is reducing your scene partner to some primitive thing to be placed on a shelf, shutting out others until they are no longer able to bear witness to you.

I hope I can be a good actor. And a dancer. And a mime. And a puppeteer. I want to. I’m really trying. This year, I've begun to think that puppets can help all of it — these are high stakes we're dealing with, but it’s hard to take yourself too seriously while wearing little monkeys on your fingers, and I think that’s a great thing to remember. Just for fun, when returning to the States, for the first time I tried putting “puppeteer” under the occupational heading on my disembarkation card. When I gave it to the woman at the booth, she saw what I’d written, chuckled, and asked, “So, what’s that like?”

“It’s nice,” I replied. “You get to make funny sounds.”

She paused for a moment, then smiled and sent me through.

And The Gods Play On

There is a home video of my Wayang Kulit teacher’s daughter playing with his puppets. She’s only three years old in the footage and her head barely reaches the bottom of the puppet screen. That doesn’t seem to bother her, though — sitting there at the base of the frame, she swoops one character up into the playing space with a quiet and determined focus. She moves its arm to touch another character’s face. She takes up the other character, too, and is soon pushing them together into an embrace that’s all the more endearing for its clumsiness. Her attention never strays from the puppets.

This is a girl who, now, a few years older, has become a perennial performer. She actively seeks out cameras, always wanting to show off the newest dance she’s picked up from youtube — and even more interested in subsequently watching herself in playback over and over again. Yet, in this video, as a little three year old, she never once turns to the camera. In fact, nothing about the video feels like an outright performance, at all — and why should it? This isn’t a puppet show for anyone but herself.

That was the only way he could capture the moment, my teacher interjects as we watch the footage one day. He begins to explain to me his frustrations surrounding the event: how, back then, his daughter would outright refuse whenever he asked her to perform for his friends; how she’d run away when he would ask again. If she’d known he was secretly filming her, she probably would have stopped then, too, he reasons. I tune my attention back to his daughter in the film. Now and again, I can barely make out her voice as it softly alternates between the two figures, creating dialogue and monologue, together. My daughter is fickle, my teacher mutters quietly.

I’m trying my best to recount this scene without over-sentimentalizing it, or, even worse, smothering it all together under too much “adult-speak." (Run, don’t walk, should you read the word “ludic" anywhere in this post.) Suffice it to say, the whole thing was beyond adorable — even as it was an all-together everyday moment. What little child hasn’t, at some point, played with their dolls or LEGOs or stuffed animals or miniature dinosaurs or pieces of fabric or a collection of sticks (and so on, and so on), bringing imaginative life to beloved toys and making everyday things a little more fun and personal? And what little child hasn’t done so in a way that was near exclusively intended for his or her own enjoyment? Entry into someone else’s imaginary (magical?) world is rare thing. Such places are expansive but fragile; you must tred lightly, careful not to break any rules you never knew existed — they do exist, they always do, and they’re integral to the reality of the place.

There was a while when I was younger — though older than three (and post Dog-and-Dog-and-Pillow days) — that my best friend and I got really into professional wrestling. Before we could get our hands on real action figures or any of the video games, we built three dimensional wrestling rings out of construction paper where we’d stage never-ending feuds between hand-made, cut-out paper figures. It was always too complicated to fight each other, so we’d take turns, each getting our own chance to play both characters, ring-side announcer, sound effect man, and crowd all at once. Watching this video of my teacher's daughter led me to think about those wrestling matches for the first time in years. I remembered how close I felt to that friend, how even with another person at my side, those matches were play, not performance. It makes me wonder whether that had had something to do with us being best friends.

When I return my focus to the video, though, it all suddenly feels different. Here was a three year old playing, but she's doing so with her father’s Wayang Kulit puppets, specifically. All-too-smooth universal associations aside, there are some undeniably specific cultural curiosities peppering this video. The skinny character with the elaborate headdress, for example, has his back arm positioned just right, so that its elbow carves a deliberately acute angle back towards its waist. And each puppet enters and exits in precise arcs, following trace forms that — I now know — are essential for casting expansive shadows upon their backdrop. And it's here that, as so often this year, something at once profound and obvious hits me: this is play and not performance, but it is also tradition. Sitting at her father’s screen, my teacher’s daughter was acting like any other little girl but also already training to become a dalang puppeteer.

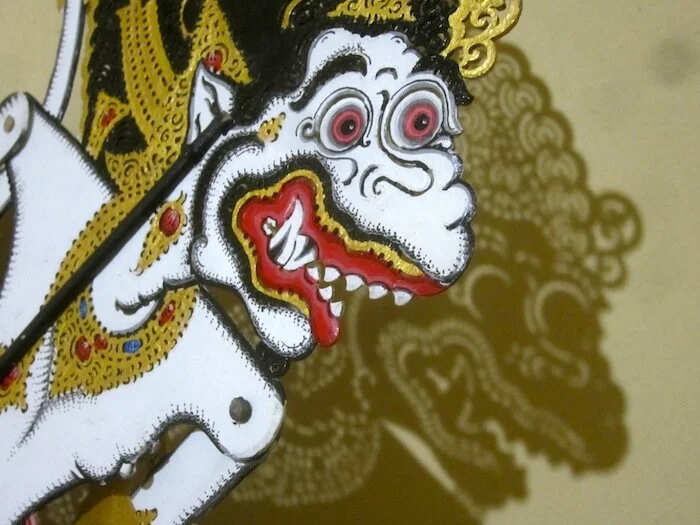

Of all the forms of puppetry I’ve learned this year, Balinese Wayang Kulit puppets are the simplest to individually manipulate. There really is something childlike in the way they move. Built from cow’s hide and manipulated from below, Wayang Kulit rarely have more than three points of individuated articulation. Each puppet is stabilized by a thick rod running up its middle. Some characters’ arms move on their own, with additional, thinner rods affixed to their hands that stretch down long enough for you to hold in yours, and the clown characters can move their mouths by pulling on a string running from the lower jaw to the base of the rod below. But — save a few special exceptions — that’s it. As dalang, you are the show’s only puppeteer. It is your job to bring these puppets, often as many as thirty or forty per show, to life. Should you need to control more than one puppet at once, you’ll usually be limited to a single hand per puppet, further reducing each character’s movement to a vocabulary of full body swings and turns and jumps and shakes. When two puppets fight, it’s not all that far removed from my days staging wrestling matches; figures fly around the playing space, full bodies collide, and only in special, intricate moments, will the more articulate arms come into play, with one puppet grabbing the other and tossing him about.

Artaud once described Balinese actors as animated hieroglyphs but the definition feels far more literally applicable for Wayang. These are figures forever confined to two-dimensions. Many characters feature designs that straddle front and profile views simultaneously— sideways heads and feet improbably cut by torsos turned directly towards their audience— but even these geometric twists are rendered flat on the cow’s hide and by the shadows they cast.

For all their limitations and lack of dimensions, though, Wayang Kulit puppets come to absolute life under the care of a skillful puppeteer. Their shapes speak words and their interplay makes sentences. Up on their screen, broad gestures gain new subtleties. A male puppet’s two arms dance around its waist until suddenly, with a swift diagonal motion, you realize that he’s tying his sash. Soon after, a clown character grows all the more arrogant and absurd through his continued attempts to turn his back on his comedic foil mid-conversation. I know this guy — you think as he moves from side to side, mouth furiously flapping to match the dalang’s snorting laugh. And then there are the shadows; each puppet is in constant collaboration with the fire hung less than a foot behind the screen. With nothing more than a quick shift of a puppet’s orientation to the flame, a single arrow can suddenly fire twenty times at rapid speeds by transforming back and forth from its realistic shape to a jetting streak of black. A worm can grow into a dragon by pulling the puppet closer to the flame, casting a larger, more terrifying figure on the screen. And even when a puppet remains still, its base rod affixed into material beneath the screen so it can remain onstage without being held by the dalang, its shadow continues to dance. As the flame moves, so does the puppet’s silhouette.

There is Arjuna, the crafty prince; Hanoman, the monkey king; Twalen, a lazy, overweight servant for protagonists; Delem, the boisterous, over-energetic aid to the antagonists— these are characters known by everyone who comes to see the show. Night after night these characters enact the same stories of princes and demons and animal lords locked in battle, tested by the gods, or spurned by love. Even as the plot varies from show to show, the super-structure remains the same. Protagonists enter from the dalang’s right, antagonists from the left. Love and seduction scenes come early, then travel scenes, then the big battles. The stories play out like animated comic books, fitting all the action within that familiar, rectangular frame, and supplanting all those explosive SMACK, POW, and THUD word bubbles with the percussive sounds of the cepalo, a wooden hammer clutched by two biggest toes on the dalang’s right foot that is rhythmically beat against the side of the puppet box throughout the show.

The use of this cepalo might help to hint at how much more than puppet manipulation a dalang must do. Beyond animating the puppets, during a performance the dalang must voice all the characters, speak in two to three languages, sing in ancient Kawi, relate all scenes and puppet movement to the accompanying Gamelan music, and join in the music by striking the cepalo. Get ready to improvise, too; not once have I seen an actual, written script, and local audiences aren’t too forgiving when they watch over-done gags or hear recycled material. Within the set format, clown characters may pop up whenever they so please, doling out tangential jokes, running vaudeville gags, even providing meta-commentary on the night’s offerings. These are some of my favorite moments in a Wayang Kulit show. The physical humor transcends language my barriers — though whatever they’re saying must be pretty good; I’ve seen audience members laugh so hard they’ve fallen out of their seats. During these moments, the dalang feels almost like a stand-up comedian, one who uses puppets to deliver his jokes from behind the screen (multiple dalang I’ve met work as bondres, masked clowns, as well). These bits can carry on for so long that you almost forget there is a plot, but then suddenly Bima, the warrior prince, comes crashing across the screen in a tussle with a large demon, and the story continues right where it left off.

As you watch Wayang, you’re not restricted to any one area of the performance space. If you’re tired of viewing the shadows, you can get up and walk behind the screen for a look at the dalang as he (or she, though usually he) conducts the evening’s adventure. Despite all the disjointed multitasking, the backstage atmosphere at a good Wayang peformance is strikingly calm. Assistants to the dalang prepare the next puppets for their entrance and tend to the flame while the dalang bounces from character to character, swinging his voice from high and nasally to deep and guttural with astounding ease. It’s easy to run things at a frenetic pace, but the best dalangs can always turn at a moment’s notice, throwing puppets around before stopping all at once to deliver a punchline.

But even watching from behind the screen cannot offer a complete picture of the dalang’s role; though a puppeteer, a dalang is equal parts shaman and priest, as well. He is a conduit of the cosmos. He begins every show with prayers to the Gods, seeking permission and assistance in the task of replicating their roles in miniature. The white screen that houses the night’s shadows mirrors the holy emptiness from which the world sprung — a fact acknowledged in a passage of ancient Kawi language that opens all traditional Wayang performances. It’s no coincidence that the vocal inflections and rhythmic patterns accompanying a dalang’s Kawi recitations sound so similar to the Kawi recitations heard at religious ceremonies, weddings, and offerings.

The dalang’s priestly and shamanistic duties come out in full when he is tasked with transforming normal water into tirta, holy water blessed by the gods and sought by ailing individuals who require purification. Following a special performance, specific puppets are positioned onscreen to create a holy tableau that will bear witness to the offerings and transformation. Flowers are placed in some of the puppets’ hands. The dalang performs a series of mantras and incantations while interacting with an elaborate system of offerings and religious instruments. Beginning with his puppet of the God Siva, the dalang stirs the tirta water with the base rods of the puppets in the tableau. Through the puppets, the gods reach the water. When the ritual is complete, the puppet screen is removed to reveal the intended recipients dutifully seated on the other side of the puppet frame. With tirta water in hand, the dalang blesses the recipients across this threshold at once literal and symbolic.

I was completely caught off-guard by the first purification ceremony I witnessed. Armed with a description similar to what I recounted in the previous paragraph, I assumed that the ceremony’s preceding puppet show would reflect the piety of the occasion with an appropriately austere performance. Instead, a massive demon soldier puppet suddenly appeared on the screen with a great spear in both hands and a penis twice as large. This other weapon had its own stick for manipulating and would rise and fall in coordination with the demon’s high pitched cough. For the next fifteen minutes, I watched in hilarious disbelief as one of the clown characters — who, up until now, had been head-butting his enemies in the crotch — tried to figure out how to defeat his most formidable opponent yet. The audience ate it up. Forty-five minutes later, they sat respectfully quiet as the holy water was blessed.

It’s experiences like these that leave me feeling like I’m always at least one step behind whatever’s happening in Wayang Kulit. That’s not at all a bad thing— I should add— and it’s hardly surprising; Wayang Kulit is thought to be the oldest form of puppetry in all of Asia — centuries of culture and tradition have been distilled into these two-dimensional figures made of cow’s hide, black leather sealer, and acrylic colors. To study Wayang Kulit is to be thrown right into the middle of it all, and even more so if you’re entering its surrounding culture for the first time.

In the days leading up to my first performance, I felt particularly overwhelmed by all that I was stacking up against. There was just too much to learn— too many disparate skills to practice, too many languages to remember, too many cross-cultural peculiarities to bridge. I kept dwelling on something Jerzy Grotowski once wrote: A Westerner doing “Oriental" theatre is either "free" - and thus like a monkey imitating his master, making pseudo-signs without precision or usefulness, trying to find the “forces" manifested by actor/mediums, etc …. the affective imagination — or else he is a near-perfect Balinese, though not quite so good. Except, words twisted in my memory, all I could remember was that my two best options were to be a performing monkey or simply not as good as local.

At the top of the show, as the overture began, my timing was off on a few of my first cepalo strikes. I winced. Already, I was making a mess of things.

But the show went on, no problem. When you get down to it, it’s really just me and puppets back there — so long as I didn’t stop, no one else could. By the end of the opening scene I had loosened up. Jokes came easily, sudden improvisations surprised even me, and people laughed. This wasn’t so different than my paper cut-out wrestling matches, after all— and “broad humor" is called so for a reason. By the end of the show, my right leg had gone numb from gripping the cepalo and striking the box. My voice was ragged. A few embers sat in my lap, loosened from the torch when a dragon puppet’s tail swung wildly at its eagle opponent. Never before had I sweat so much while sitting down. But I made it through, and it was pure fun.

There’s a whole lot about Wayang that plays out like that. Amidst the whirl of activities and sectioning of brain activity, you get to sit beneath the stars and tell stupid jokes that are somehow much funnier coming out of the mouths of puppet shadows. Characters speak in voices and sounds you stopped making when you turned fourteen and decided to “be mature" (next time you run into me, ask about the Wayang monkey voice). And when it’s all over, you’re just a guy again— most of your audience usually leaves as the show is wrapping, wisely recognizing that all the best parts have come and gone. It’s grounding, even as it’s fleeting, as exhilarating as exhausting.

Most of all, participating in a Wayang Kulit show — be you performer or audience —affords you the opportunity to share in an ancient tradition that is still thriving today. The performance culture surrounding Wayang Kulit feels equal parts respect for its own history and attention to little shifts in local life. Somewhere in every show you will find a quixotic collision of now and forever — a demon from the Mahabharata gets compared to Jet Li, or Siwa’s older brother meets a puppet with jerry-curl who speaks in gibberish skat and finishes every sentence with the word Jazzzzzz. Some things stay from night to night and century to century; others come and go, conceived by a dalang’s imagination but given life — or killed off — by the public. I think it’s this marriage of the longstanding and the one-time idiosyncratic that allows a three-year-old’s playtime and a holy ceremony to juxtapose so easily within the same evening. Everywhere you go, puppets are serious, religious figures. They hang on walls to invite good energy into a room. They have their own temples and holy days. They are to be treated with respect (whatever you do, don’t step directly over one). At the same time, they’re never treated with the kind of perverted preciousness many religious figurations receive in the West. These are mystical hieroglyphics, but dammit, if they want to fart on screen you can bet they will— and most people love them all the more for it.

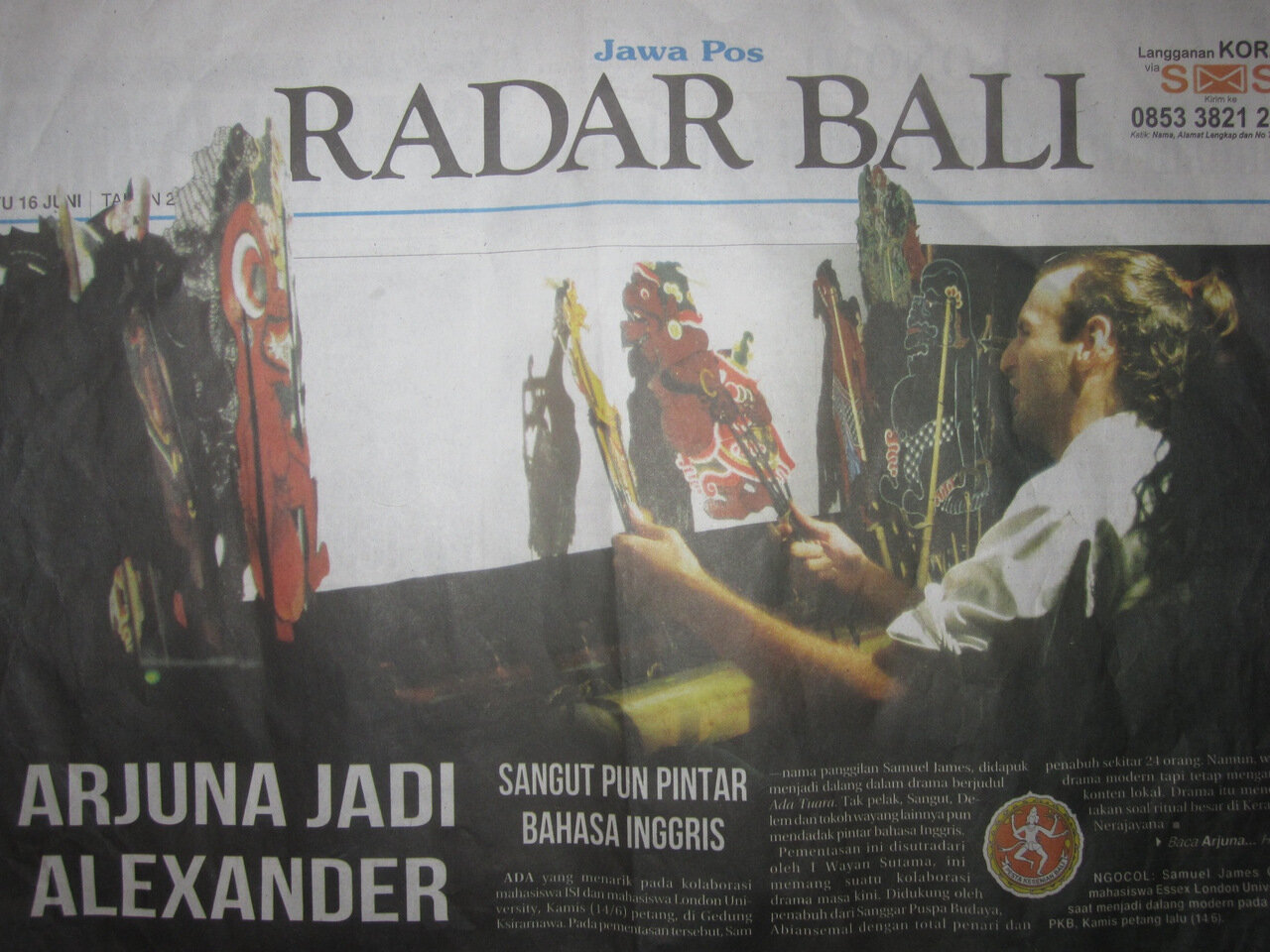

I gave my first full-length Wayang Kulit performance a little over a week ago. A clip from the show made it online so I figured— why not post it up on the blog, too?

Those good old nerves were acting up for this one more than for anything else I’ve performed in quite a while, but once the show got going I tried my best to loosen up and just have some fun. Watching the playback, I can see plenty of room for improvement all over— I think priority numero uno is developing a stronger awareness of the play between my light source and shadows (if only to better keep my hands out of view). That’s all par for the course, though, considering I’ve had only about two months of training so far. Those who came out to watch— English speaking and otherwise— all seemed to enjoy themselves, which is always a good sign. As for me, I’m just happy to now know that I can do it!

Plenty more words about Wayang to add to the blog soon, but in the meantime I hope you enjoy the show.

Notes from the Body

In Prague I began my Watson year by studying wood carving for marionette construction. It was an exercise of negative creation; you chip away at your material until, miraculously, a figure emerges. In Abian Semal, a small village in Bali, I recently attended a tooth filing ceremony. This was a ritual of blunting revelation; they filed away at your sharpest fangs, rounding off any demonic semblances until, as expected, your more human figure emerged.'

In London I met a woman who suggested that the first puppet I ever encountered was my own skeleton.

In Kyoto I met an antique dealer who kept Bunraku heads, arms, and whole bodies among his collection of Japanese relics. Here I explored the inner mechanics of Bunraku manipulations: stick your left arm into the puppet’s back and grab hold of its neck where you’ll find a small network of levers affixed to strings running out into the puppet’s head. Pull the left one and the puppet blinks. Pull the front one and its head snaps into place. Only days earlier in Tokyo, on the recommendation of my friend Daiji, a Butoh dancers, I had booked an appointment to receive a special kind of single-needle acupuncture. It was invasive and intense. The acupuncturist, a former dancer himself, asked, "かんじる?"— do you feel it?— after every insertion. The correct answer was always yes. You were meant to feel the needle enter your body, meant to experience the resulting waves crashing beneath your skin, appearing out of nowhere yet clearly emanating from the tiniest of source points. Stick my right calf and my hip socket throbs. Stick the inside of my thigh and my big toe twitches uncontrollably.

Here in Denpasar, I slightly dislocated that same big toe last week after a night of barefoot Futsal with friends. It wasn’t awful but it was enough to impact my stride and my landlord’s son noticed. He recommended I show it to his father, who I guessed was an expert at this sort of thing based on his son’s broken English and the popping sounds he made as he pantomimed an invisible limb. The next day, his father prepared a small bowl of water and a vegetable that looked like a shallot. He cut the vegetable and mashed it in the water while reciting a prayer, then spread the mixture all over my foot. He pressed and kneaded into my leg. He massaged the top of my foot with his thumbs until the veins shown blue beneath the surface. He pressed into the middle digit of my second smallest toe, sending a searing sensation up my leg and into my face, clouding my vision. Letting go, he placed my two feet together and pressed into the space between my big and second toes with the tips of his biggest toes. From this position, we held hands as I stood up and sat down six times. Finally, he let go and asked how my toe felt. It was perfect. I was able walk as if nothing had happened— and indeed, I understood very little of all that had just happened.

Recounting these experiences, I feel myself growing newly aware of the beguiling honesty buried within the words, “second-nature". I see how the exuberance found in assimilating things formerly foreign can easily obscure an integral truth so clearly contained in the very construction of the phrase— that these are second-tiered masteries, at best. Breathing isn’t second nature, it is nature itself. But movement, our own bodies— these remain questions for me.

If there is any truth to be found in what I was told in London, if our own bodies really are our oldest puppets, it is a truth that I find difficult to comprehend from moment to moment. My own skeleton is hardly a foreign object; it ceased to be so soon after our first introduction. Over time, I grew so proficient at its daily manipulation that I stopped seeing it as manipulation at all. I had swaddled my skeleton. Physically inhabiting space— piloting my own body in real-time— no longer seemed miraculous; it was second nature. But this year has served me a global flow of contrarian reminders. I can no longer brush aside the gnawing fact that something alien lies buried deep in the relationship I keep with my own body. Though our now-twenty-three-year-old partnership feels like an old embrace, only my muscles know its deepest contours. Only they know the secrets resting in those most intimate pockets, secrets that they, too, have swaddled. My muscles have pressed these secrets so firmly against my bones that they are now etched into the calcium as invisibly as the prayer that my landlord silently etched into the shallot-like vegetable when he fixed my big toe.

I already feel that the deepest, most preciously kept answers to these secrets will remain inaccessible, inside me yet forever out of reach. It seems to me that they have been designed so as to be taken to my grave, only to be made visible after all that covers them has turned to dust. Nevertheless, I will continue to seek them out as I live. In my travels, I have found that this search can be an act of positive reverence; rather than hacking away at what we have in search of things buried beneath, we create metaphorical bodies and physical fictions as a way to pay our respects to mysteries at once too foreign and intimate to ever fully comprehend.

Rangda

Amidst the melodic twang of the Gamelan, a woman wails from somewhere across the street. A moment later, she emerges from the crowd, supported by two men. Her eyes are clamped shut, her mouth looks like it has been pried open, and her hands shake in complex, nearly a-rhythmic patterns. She does not resist the men who guide her towards the temple entrance, but she moves slowly with knees bent at an angle that matches her elbows, now raised above her head.

For a brief moment, the music falls into one of its periodic lulls. My friend Kadet leans over to me and says, “Oni hairu," Japanese for “A demon enters." Kadet doesn’t speak English. We hit it off last week when we discovered that we both speak Japanese. Meeting outside both our communicative comfort zones in mutually foreign language has made for a pleasantly liberating form of conversation here, one that we have enjoyed together over many recent evenings. In the daytime, Kadet plays the Rindik— an instrument that’s kind of like a bamboo xylophone— at a few different hotels around Sanur, but tonight he is playing whatever instruments are required of him within this Gamelan that provides the music for a local Barong dance. He invited me to come along and I eagerly accepted. Long have I wanted to see a real Barong, the ceremonial performance enacting a never-ending struggle between the Barong, the four-legged God with protective powers, and the demon witch Rangda.

A demon enters— which is to say that, across the street from where we sit and Kadet plays, a woman has been possessed by Rangda. She has entered a trance. Before long, three or four other woman have appeared, differently pitched wailings emerging from newly contorted bodies. The village priest, who has stood by throughout the performance like a referee in a boxing match, ushers all but the first woman into the temple. While the Barong and Rangda enter into their climactic fight of the evening, this woman alone remains alongside the entrance to the temple grounds. Her body, still held in abnormal angularity, sways and steps slowly with the music. With little fanfare, the Barong succeeds in temporarily overcoming the demon, and Rangda is escorted back into the temple. Though her eyes remain closed, the woman follows closely behind. As they depart, the two walk with strikingly similar rhythms and movements. The performance is over and the bulk of the audience start to head out. Shortly after, the formerly stricken women emerge from the temple entrance one by one, walking home with not so much as a hint of what had happened just five minutes earlier.

Allow me to play the skeptic for just a moment, if only to get it out of my system… It seems to me that although the movement vocabulary newly produced by these entranced women bore no resemblance to their everyday movement, it was not exactly removed from Balinese daily life. Though I’ve only been here for a few weeks, I already get the impression that the dance, music, and theatrical representations of religious stories are integral elements of the local society. I’ve yet to see a single written document detailing the stunningly complex musical scores, minutely detailed choreography, or ancient Indonesian texts. Everything is memorized, internalized, and then improvised. And so, whether or not the entranced women were formerly dancers or performers is somewhat irrelevant— simply growing up here seems to cultivate a capacity to perform somewhere within you.

Okay that’s done with. Really— its is all I’ve got for the case of incredulity. Be it demonic possession or some other, intangible force, something changed in these women. They seemed to have been taken elsewhere, their bodies gaining new life in the process.

I’ve written about empty vessels on this blog before— indeed, this is often the cardinal strength that human performers seek when they look towards the puppet for inspiration. Striving towards an inanimate ideal, these actors try to develop a powerfully absent presence, one within which audience members may feel more willing to find character, emotions, or even themselves. But this was something different. Manifesting from a place of absence or not, here something else took over, a new presence emerging from a familiar vessel. It was gripping and just a little bit terrifying.

Throughout the evening, the two men performing as the Barong would be periodically changed out for new performers. To do so, the Barong would cross back to its initial location in the street and two locals would quickly run out from the crowd, getting beneath the creature’s costume to support this transition of hosts. The now finished performers emerged from beneath the costume and joined the two new performers at the God’s head for a moment of prayer. Following, the two new men assumed positions within the creature, and the Barong sprang to life once again. There was no attempt made to hide this transition; the Barong was still the Barong, despite its new inhabitants.

Whether or not the same could be said for the women in trance, I just don’t know. Kadek and his friends in the Gamelan didn’t seem too disturbed by the event. They continued to crack jokes and pass around a couple bottles of liquor while hammering away at their musical instruments. They kept wickedly fast tempos. Their music played on until the very end, at which point they, too, packed up their things and we all went home.

It is March 23rd as I am writing this. Today marks the start of the new Hindu year and people here in Bali observe the occasion with an island-wide day of silence. No cars or motorbikes are permitted to fill the usually busy streets, nor fire or artificial light for illuminating people’s homes. The airport in Denpasar has shut down for the day and work has been cancelled all across the island. For the stricter observers, there is no going outside and for the strictest, no food or water and no speaking aloud. To close the year, yesterday was the day of Ogoh Ogoh.

In the weeks prior, villages all over Bali had been preparing at their Banjar by building massive statues from styrofoam and wire-mesh. As with the majority of stories told in Bali, many of the characters and scenes depicted came from either the Mahabharata or Ramayan, religious texts epic in scope and adventure. This was not a strict requirement of the Ogoh Ogoh festivities, though, and a few of the statues definitely exhibited imaginations run wild. I took these photos this past week while taking mini Ogoh Ogoh sightseeing adventure with friends. I tried to pick some of the best shots for the ten photos posted above and, not-coincidentally, most that made it up come from yesterday’s parade in the heart of Denpasar where the best of the best from nearby villages came to compete for the prize of Ogoh Ogoh of the year.

I don’t believe that any Ogoh Ogoh statues were on display at the 1931 Paris World Exhibition where Antonin Artaud first saw the Balinese performances that would later lead him to write about Balinese arts and theatricality in such laudatory tones. Still, as I looked at all of these giant, fantastical creations, I was reminded of his writings on the Grotesque and that powerfully visceral visual poetry— separate from a play’s text— that he felt was so missing from then contemporary western theatre. The size of these Ogoh Ogoh dwarfed their on-looking public. Because of their light-weight and gravity-defying poses, many would shake in the wind, bobbing back and forth just enough make me think— if only for a moment— that they moved all on their own. Animation or no, the streets of Denpasar felt particularly alive all day, with Gods, Demons, and hordes of people coming out to celebrate the end of year and the Ogoh Ogoh.

This all culminated in the day’s main event, a evening competition that saw every village’s Ogoh Ogoh parade through their local area of Denpasar, attached to a slatted bamboo base and carried by around twenty men. Just about the entire village comes out in support their Banjar’s statue, moving en mass alongside their Ogoh Ogoh and accompanied by their own mobile Gamelon. It was quite the event.

The Tangled Web of Robotic Takeover (ロボット, Part 1)

In 1921, Czech brothers Karel and Josef Capek introduced the word ‘Robot’ to the world with the premiere of Karel’s new play R.U.R. or Rossum’s Universal Robots. The play is set on an island factory where Domin, the General Manager of R.U.R., oversees operations in a thriving robotic service industry, creating and selling Robot laborers to clients around the world. In a plot that will probably sound all too familiar today, the use of these Robots quickly expands from general services to military operations and soon every country is using robots to fight in their wars. Eventually, the Robots decide that they’d rather not destroy one another in the name of their human masters and instead unite against their former owners, culminating in a violent take-over of the island from which they first originated. (And that’s just Acts 1 and 2.)

I wish I could show you photos from the earliest productions, but the Gods of the Internet seem to have banished what few exist far beyond the realm of free domain. Were you to perform a google search for images related to R.U.R. today, the majority of black-and-white photos that you will find come from a production dating almost twenty years after its premiere, the 1938 BBC Television version. The Robots in these photos are in fact men dressed in costumes that could easily serve as forefathers to the Tin Man from the The Wizard of Oz; with boxy shoulders, geometric head pieces, and metallic fabric abound, the production’s machine-man aesthetic easily fits into the typical image of early modern Western robotic representations. Indeed, when England produced one of its first nationally trumpeted robots in the late 1920’s— a figure surprisingly similar in appearance but, this time, actually machine— they slapped the letters RUR on it’s chest.

Yet these metallic, mechanistic visions are all far cries from Capek’s original play. As Capek outlines in the play’s Dramatis Person ae, the Robots in R.U.R. are supposed to appear far more human than machine, a design concept he intentionally plays up for uncanny comedy in the show’s prologue. Set 10 years before the play’s first act, the prologue to R.U.R. introduces the play’s pseudo-heroine, the concerned citizen and necessarily beautiful Helena Glory, who has come to Rossum’s island to argue on behalf of Robot equality. Despite her impassioned belief in the rights of robots, however, Miss Glory fails to realize that the majority of the island’s residents and employees are, in fact, robots, themselves. Recognizing this, Domin calls in his robot Secretary, Sulla, to introduce herself to Miss Glory. Capek writes:

DOMIN: Sulla, let Miss Glory have a look at you.

HELENA: [stands and offers SULLA her hand] How do you do? You must be dreadfully sad out here so far away from the rest of the world, no?

SULLA: That I cannot say, Miss Glory. Please have a seat.

HELENA: [sits down] Where are you from, Miss?

SULLA: From here, from the factory.

HELENA: Oh, you were born here?

SULLA: I was made here, yes.

HELENA: [jumping up] What?

DOMIN: [laughing] Sulla is not human, Miss Glory. Sulla is a Robot.

HELENA: I beg your pardon…

DOMIN: [placing his hand on SULLA’s shoulder] Sulla’s not offended. Take a look at the complexion we make, Miss Glory. Touch her face.

HELENA: Oh, no, no!

DOMIN: You’d never guess she was made from a different substance than we are. She even has the characteristic soft hair of a blonde, if you please. only the eyes are a bit… But on the other hand, what hair!

As the prologue continues, we learn that Old Mr. Rossum, the inventor and scientific progenitor of said Robots, originally set out to manufacture actual human beings. But Rossum’s young nephew, more a man of business than science, found his uncle’s assembly process too long and complicated. Eventually locking his Uncle in the lab, Rossum the Younger takes it upon himself to streamline the process. In a speech recounting this history to Miss Glory, Domin says:

"Young Rossum said to himself: A human being. That’s something that feels joy, plays the violin, wants to go for a walk, in general requires a lot of things that— that are, in effect, superfluos… [So] he chucked everything not directly related to work, and in doing so he pretty much discarded the human being and created the Robot. My dear Miss Glory, Robots are not people. They are mechanically more perfect than we are, they have an astounding intellectual capacity, but they have no soul."

It was Josef, Karel’s brother, who first suggested the name ‘Roboti’ for Karel’s newly invented, soulless workforce. A play on the Czech word ‘Robota,’ which means “Serf Labor" or more figuratively, “hard work," ‘Roboti’ was fun to say and captured the essence of the idea without hitting you over the head with it (prior to ‘Roboti,’ Karel was considering ‘Labori’). Ultimately, Karel liked the idea enough that the name stuck— though sometime before the play’s premiere, “Roboti’ got shortened to just “Robot."

Of course, all of this etymological history would not have mattered had the show flopped, but R.U.R. was a big hit, launching Karel Capek’s career into the international spotlight. New productions of the show soon spread to other countries, but with each new translation, the word “Robot" remained the same, too irresistibly catchy to localize. Quite quickly, the word ‘Robot’ began to mirror its namesakes in the plot from which it sprung, eagerly received as newly imported vocabulary around the word. ‘Robot’— that broad signifier of all artificial humanoid inventions designed to be loyal servants to their human masters— had become a world-wide linguistic phenomena.

Except for in Japan… kind of.

To be clear, R.U.R. was quickly translated into Japanese. It enjoyed its first localized run in 1924 at Tokyo’s famous Tsukiji Shogekijo, and it did manage to kick off a new debate among Japanese intellectuals about the role of robots in daily life. Along the way, however, it received a unique verbal facelift. In Japan, the title to Capek’s play— along with the word ‘robot’— was translated to Jinzo Ningen (人造人間), a Japanese phrase better translated back into English as “Man-made Man". Disconnected from its etymologically Slavic (and slave) roots, Jinzo Ningen emphasized the invented origins of these artificial humanoids over their intended purpose. To me, it’s a phrase that feels somehow less sinister— or at the very least, less value-laden— than its Czech original, a celebration of man’s inventive drive in lieu of a dark reminder of his desire to dominate all that surrounds him. And indeed, although the dramatic content of the play remained unchanged, Japanese audiences were described as responding to Capek’s play, and these new Jinzo Ningen, with far more curiosity and excitement than fear.

Today, the term Jinzo Ningen has fallen from colloquial use in Japan, replaced by Robotto (ロボット), the Japanese phonetic approximation of Robot, which first entered into the Japanese dictionary in 1928. Although the ascension of Robotto may have placed Japan back instep with the rest of the world’s robotic lexicon, their unique detour feels significant to me, signaling something palpably real yet difficult to decipher, something that rests within those murky confines wherein fact and fiction collide in real-time.

Is there a Japanese equivalent to Baudelaire’s “The Philosophy of Toys," I wonder, in which Baudelaire tells the story of smashing a child’s doll, fervently driven by the question “Where is the soul?". The most typical American descriptions of Japanese culture suggest that there isn’t— nor that there should be, thanks to Japan’s thoroughly non-Western religious traditions. Answers like this one, found in a Time Magazine article, invariably point to Japan’s Shintoist religion, “which," as the article writes, “blurs the line between the inanimate and animate, and in which followers believe that all things, including objects can possess living spirits." Factual validity of this answer notwithstanding, the certitude with which it is so frequently cited doesn’t sit well with me. It is, at the very least, lazy. More troublingly, to me it has faint whiffs of those unfortunate, still-lingering Orientalist airs that often hover around Occidental befuddlement over Asiatic culture. I don’t mean to suggest that a culture fostered in part through uniquely Japanese religious practices hasn’t impacted Japanese perspectives in ways significant and different from mine, but saying that Japanese people love Robots because their history of animism makes them believe that Robot have spirits would be like saying that Anglo-European people hate Robots because their history of Judeo-Christian monotheism makes them believe that Robots mock the powers of God, the sole Creator. There is a lot of good stuff to work with in there, but such a neatly rendered presentation belies a much more tangle, fragmented, and overlapping reality.

And then of course, there is my perspective on this multi-cultural phenomenon, too— a perspective that is a no less complicated mess. Before beginning my Watson, I had never read anything by Karel Capek, nor did I know the etymological history of the word “Robot," or that R.U.R. was received so differently in Japan than in Europe and America. None of these facts, however, have since come as great surprises to me. That the first Western use of the word “Robot" should fit so snuggly within what Isaac Asimov has dubbed the West’s “Frankenstein Complex"— that is: Man builds Robot, Robot kills Man— made perfect sense to me; it is but one example plucked from the longstanding history of Anglo-European technological paranoia complexes, a historical narrative sometimes easier for me to accept because I was raised within it. That this same Robotic story should be met with far less terror in Japan somehow also felt right to me— though again here, it is difficult to chart where actualities end and self-fulfilling stereotypes begin.

The 1950’s, for example, mark an important moment in the cementing of Japan as a world-wide ‘Robotopia.’ This was the decade within which Japanese robot toys first proliferated throughout the United States. But the United States deserves just as much credit as Japan for this stateside influx of little tin men. The aftermath of World War Two had left Japan in shambles. Formally occupied by the United States, early post-war Japan subsisted on hundreds of millions of American dollars delivered in the form of loans and emergency food supplies. But America wasn’t about to give so much without asking for something in return and— whether from an interest to help jumpstart the Japanese economy or out of pure quid pro quo— they soon summoned representatives from former Japanese cottage industries to the Occupation headquarters in Tokyo to discuss new exports. By the end of 1945, mere months since the war’s conclusion, the Japanese toy industry was already showing new signs of life, reassembling itself in preparation for its new client: American children. And these Americans— the boys in particular— wanted Robots.

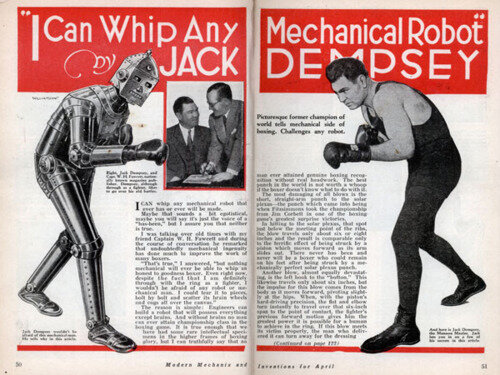

At this time, America was finally coming out of a period of smoldering robophobia that, by no coincidence, had been chronologically linked to the Great Depression. Fueled by a fear that advances in technology would soon leave the already largely unemployed population permanently out of work, the 1930’s American public had come to see Robots as symbols of displacement and of the unknown. Despite the fact that the world was still decades away from the first real, practical mechanical worker, stories in newspapers, magazines, and on the radio poured out, eagerly topping one another with newer, more fancifully terrifying creations. And because the people’s collective imagination far outmatched the technology of the times, their inability to actually produce these mechanical villains left them all the more menacing. Imaginary or not, however, good, decent, hardworking Americans were not about to go down without a fight, propelling the United States into a fanciful and purely fictional war with robots years before our impending war with the Axis. Check out one of my favorite ‘wartime’ examples, this feature from a 1934 issue of Modern Mechanix:

Following World War Two, fears of a robotic economic take-over fell alongside the American unemployment rate, but kids who grew up during the Robot threat were not about to forget their parents’ old enemy— and really, when you’re a kid, what is ever cooler than the stuff that makes your parents’ blood boil? And so, in the age-old ritual of inheriting your fore-father’s corrupting culture, the menacing imagery of these cold, steel beings grew even more widespread than before, transferring from one generation’s paranoiac prophesies to the next’s science fiction odysseys. And it was at this point that Japanese toy makers entered the picture, repurposing their popular tin toy industry to make Robots just as the Americans wanted them: geometric, mechanic, and menacing.

But Japan already had a few fictional robots of its own. In 1934, the same year that Jack Dempsey wanted to go robo-boxing, a Japanese artist named Masaki Sakamoto introduced Tanku Tankuro, a magical robot hero. In stark contrast to the predominately rectangular visions of Europe and America, Tanku Tankuro is all round surfaces, featuring a plump human head resting atop an improbably rotund, black spherical body. His head and short, chubby limbs protrude from five of the eight holes littering his body like swiss cheese. In a manner similar to Felix the Cat’s magic bag, these holes could produce almost anything at a moments notice, suddenly transforming Tanku into, say, an airplane with wings for arms and a large propellor jutting out from his front. Readers never learned the proper mechanics behind Tanku’s construction— nor how he produced or stored so many items inside his small body— but that was part of the fun behind the guy; although described as a robot, Tanku was more fantastical than mechanical, more parts imagination than cold science.

In the comparison between Japan’s Tanku Tankuro and early Western robots, I see these countries’ contrasting relationships with pre-WWII technology, as well. It reminds me of a quotation from Osamu Tezuka, the so-called ‘Grandfather’ of Japanese Animation: “While the US. was dropping atomic bombs, the Japanese military were trying to light forest fires in America by sending incendiary balloons made of bamboo and paper over on the jet stream." Tezuka’s own Tetsuwan Atomu (Mighty Atom)— or as we know him in the West, Astro Boy— feels to me like an response to this observation, both by Tezuka and his readership. Although he was originally envisioned as a mere side character to serve as a humorous foil for human protagonists, there was something about Atom that strongly resonated with Tezuka’s audience. The boy robot quickly grew so popular that Tezuka’s editors asked him to serialize a new adventure just for Atom. In April of 1952, the same month in which the American occupation of Japan officially ended, the solo adventures of Tetsuwan Atomu debuted, eagerly devoured by fans all over the country. Atom quickly became a post-war hero for a post-war Japan, propelling Tezuka to national fame in the process.

Atom’s design combines the more magical elements of earlier Japanese robots like Tanku with the greater concern for science and technology found in the west— concerns Japan is described as internalizing following their devastating defeat. Sure, Atom has rocket propelled jets hidden in his hands and feet that allow him to fly through the air; yes, he can increase his sense of hearing 1000-fold and turn his eyes into searchlights; and okay, he can even sense the innate good and bad qualities in the people around him. But Tezuka, a doctor by training, took great care to feature Atom’s intricately designed technological innards, as well— and in doing so, he caught up his hero with his contemporaries across the Pacific. And although the technological explanations given for the boy robot’s powers never really held up (despite repeated updates to account for new developments in actual technology), they were no less fanciful than the robotic creations that had waged war with American imaginations a decade earlier. Fictional though he may be, Atom was received as a true child of science.

Tezuka took seriously the responsibilities and influence that came from his boy robot assuming this unofficial role of spokesperson for the scientific future. Atom fights for justice but, even more importantly, strives for world-peace. Deeply impacted by the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Tezuka envisioned Atom and his not-so-distant-future as emblems of the possible harmony between man and machine, a time in which nuclear power was used only for good and creative forces. And so, when he’s not defending the world, Atom the Robot goes to school, keeping boyhood friends like all other humans. He is the “robot next door," not just a protector or servant, but also a friend to all humans.

And yet, the world of Tetsuwan Atomu is not all utopic. One of the most consistent tropes in the Atom series (and to my mind, one of its most endearing qualities, as well) is Atom’s ongoing attempts to be more human— inevitably followed by the somewhat awkward, sometimes sad reminders that he will never be like his friends. His origins story tells the tale of a grief-stricken inventor who sought to fill the void left by the death of his 12-year-old son by rebuilding him in robotic form. As such, Atom does look and sound quite like his human model. But the gaps between he and his breathing counterparts are felt as all the more unbridgeable because of his almost fully human construction. Eventually, Atom’s inventor could not bear the differences between his lost son and his flawed creation, and abandons Atom on the streets. But even the kinder and more loving scientist/father-figure who later takes in Atom cannot really help the boy’s inhuman flaws, and the modifications he offers only reinforce Atom’s differences. For example, when Atom discovers that he cannot cry, his new scientist father is able to augment Atom’s design to allow for tears, but he still cannot teach the boy about real sadness. While Atom can solve complex math equations at unparalleled speeds, he struggles to understand art. And whenever he eats food, he must later open up his chest cavity and remove all he swallowed. He is, in a sense, too perfect; the only flaws in his construction are his lack of the flaws that figure so centrally into being human— flaws made all the more glaringly visible by how close he comes to us.

Tezuka claimed that a translated copy of R.U.R. served as one of the earliest and greatest influences on his robot-driven narratives, and although the more technologically advanced future of Testuwan Atomu proved quite popular, championed by Japanese children, adults and industries alike, within even the earliest Atom stories lie darker themes of discrimination and otherness. Notably, one of the few Atom episodes to feature the death of the boy-robot, the 1966 story “Blue Knight," tells the story of a failed fight for robotic freedom. The robot leader of this emancipatory movement, the Blue Knight of the story’s title, kills humans who stand in the way of robot liberation and even succeeds in founding a short-lived new robot nation called Robotania. As the story progresses, we find Atom slowly beginning to empathize with the Blue Knight’s crusade. For possibly the first time, he is depicted as questioning the logic behind the Tezuka’s Laws of Robotics, which— like Asimov’s own in the West— envision a world in which robots must put the good of their human counterparts above themselves. When humans ultimately wage war against this Robotania, crushing the Blue Knight and his rebellious robot cohorts, Atom is destroyed, as well, reduced to nothing more than one of the many mechanical causalities of the failed revolution.

Of course, Atom would return, his popularity too great to ever allow him a true death— and especially not one in so grim a manner. By 1966, Atom had become the first hero ever to be animated for Japanese Television, with translated episodes already filling American airways, as well. Today, the impacts of Atom/Astro Boy are legion, far too great to easily measure here. Perhaps all too fittingly, they also contribute to the tangled web of influences with which I wrestled earlier in this post. In no small part thanks to Atom, Osamu Tezuka is credited with first introducing and popularizing “anime eyes," those impossibly large, glimmering ovals that are now synonymous with Japanese animation. But to trace the genesis of said peepers requires yet another trip back across the Pacific; before they were drawn onto the boy robot and his friends, strikingly similar eyes were busy helping characters like Donald Duck and Betty Boop look out into the world. Tezuka is quoted as being a large admirer of Walt Disney. Early in his career, he even redrew early Disney films like Snow White and the Seven Dwarves for Japanese audiences. Disney would return this artistic appropriation back to Tezuka over a half-century later, adding one more layer to the overlapping cultural exchange.

Although Disney denies the connection, see here, Tezuka’s Kimba the Lion, alongside Disney’s The Lion King.

And as for us, today? Astro Boy’s future is now our present— or perhaps, in some ways, already our past, for the boy robot’s official birthday, April 7, 2003, has already come and gone. While the world of robot-human harmony has not materialized as Tezuka’s story envisioned, it does feel to me like the cultural grip of robotics has already become a much more casually accepted phenomenon. In some form or another, the things are everywhere. Case in point, I found this guy at a home appliance store in Denpasar shortly after I arrived in Bali. It was nestled between plates and spoons, on sale for less than two dollars.

I have no idea why it was there— and I have this impression that no one else would, either. But that’s sort of the point: unlike our fictions and fears, the real world’s robotic take-over won’t be signaled by metallic, soulless overlords but by the inexplicable, plastic decorations found in Aisle 7. It creeps up on you. First kitchenware, then the world… and whether or not that’s a good thing, well, I think it depends on who you ask.

Coming in Part 2— Freud and Friends: Charting the Uncanny Valley.

[Bibliographical Note— in addition to my travels, this post feature some facts and quotes taken from multiple books I picked up along the way. The quoted lines from R.U.R. come from Claudia Novack’s translation. The quotation from Tezuka about World War Two was taken from Frederik L. Schodt’s “The Astro Boy Essays." Another of Schodt’s books, “Inside the Robot Kingdom," proved equally interesting and useful in charting the history of robots in Japan. I suggest you check them out if you’re interested.]

Some Thoughts on the Noh

I.In the Noh, I am told, your 68th birthday inaugurates an important year in your life as a performer. Admittedly, by the time you turn 68 it has probably been 20 to 30 years since you were at the peak of your physical ability. But when you were at the prime of your technique, you had not yet accumulated the life experiences needed to best exhibit your potential. 68 is the year in which your now declining technique and your life’s life meet at their highest, most harmonious point.

II. In Noh, you might hear about the early idea that a spirit or God resides within each Noh mask and that, by putting on the mask, you are welcoming this spirit or God to fill you from within. I ask Tatsushige if he believed this and he says, well, notreally, but that as an image it is still very powerfully and good. He then pauses and says that, once— maybe in his early twenties— he did feel like the God had entered him through the mask, for just five to ten seconds. But that was once, and it was a long time ago.

III. The Noh mask is carved out of a single piece of Japanese Cypress (檜). The same wood is used to construct the Noh stage, itself.

IV. Suddenly, I need story. In the past— Watson and otherwise— I’ve often focused my training on exploring the non-narrative elements of performance, driven by faith in the possibility that the most fundamental aspects of onstage presence exist somewhere beyond scripted story. I thought that studying and watching Noh would complement this search. Witnessing a Noh performance is like smelling the bare ingredients to your favorite meal while sitting in a nearby room. It lives in reduced suggestion, attempting to perform the distilled essence of actions and feelings from stories that can sometimes already feel fantastical or esoteric. Zeami, whose writings on Noh serve as something like the Aristotelian Poetics of traditional Japanese theatre, writes in his Shikadoh treaties:

"You should know the matter of essence and function of Noh. Essence is like the flower, while function is like the fragrance. Again, this is like the moon and its light. If you are able to understand essence, function will come into being on its own. Thus, in watching Noh, those who know watch with their minds, while those who don’t know watch with their eyes. What is seen with the mind is essence; what is seen with the eyes is function."

Although I sometimes find— or am given or told— a summary of the Noh play I am about to see performed, I often enter the theatre completely blind. Reflecting on the bulk of these experiences, I was surprised to realize how even the barest of narrative outlines could so greatly help my ability to remain engaged throughout the performance. I found I needed story.

Yet, I have the impression that once I am equipped with this basic story knowledge I am elevated to a level of comprehension shared by most Japanese audience members. Often, Noh chanting is slowed and stretched to the point where words’ meanings fall way to individual sounds. Additionally, most audience members struggle to understand the chanting even when it is delivered in a more colloquial style because the classical Japanese spoken is now so far removed from contemporary language. I’ve heard a few people equate it to Shakespearean english, but my experiences have left me thinking that Chaucer might be a better analogy. Whan that aprill with his shoures soote/The droghte of march hath perced to the roote…

I sometimes see audience members following the performance with the play’s script in hand. A couple performers have told me, however, that they feel this is the improper way to experience Noh. It is too intellectual, too much viewing with just the eyes.

V. Zeami again— "Even though you may be conversant with various types of role-playing, if you do not understand what it is to have the Flower, it will be like collecting grasses and trees when they are not in bloom. The flowers of a thousand grasses and ten thousand trees are all different colors, but to the mind that sees them as interesting, they are all the same: flowers."

VI. Because the Noh is so still, so contained and so reduced, the bigger movements feel exceptionally large. One dance told the tail-end of a story about two lovers who disobey their parents and continue to meet each other in the cover of night. The parents decide to break the bridge that the two cross to meet one another, thinking it will put a stop to their romance once and for all. In the next night’s darkness, the two lovers fail to see that the bridge is broken and plunge to their deaths. When the story of the dance reached the moment that the lovers should fall, the Shite, standing on one leg, suddenly dropped into a seated position with his head hung low. The abrupt change in rhythm and unexpected fall felt electrifying. My heart pushed through my chest as if I was watching death-defying stunts, its kinetic energy echoing through the stillness and silence.

VII. The music of Noh has been unlike anything I have ever heard before. The rhythms follow 5 and 7 counts but are then fit within an 8 count, as well. Entire phrases might all fall on the same note, and when the notes do change, they do not jump in octaval patterns. Single notes are stretched and phrases build as if in conversation. I once told one performer that I can tell he knows exactly what he is saying when he chants, but he told me that, on the contrary, he often only understands a paraphrased meaning at best.

In one song, I struggle with a particularly long passage of equal length, same note sounds— つ か い は き た (Tsu-Ka-Ee-Ha-Ki-Ta). The repetition leaves me uncertain, doubting dynamics and how to fill the phrase. It all sounds the same. After a particularly frustrating go, I decide to pretend that I am secretly saying “Today-I-Went-To-The-Store." Suddenly, it all sounds much more decisive, like I know exactly what I mean to say.

VIII. While entering into the musical composition was difficult at first, I found the musical notation used in Noh very intuitive. Each note is denoted through wisps and lines that look to me like strokes of paint that might have been made by the path of the sounds. When I sing the notes of a Noh chant, I easily imagine these shapes coming out from somewhere inside of me. I pretend my voice is the paint.

IX. In addition to the chanting, one to three different drummers and a flutist accompany the performance— each with their own rhythms, as well. They bob and weave around and atop one-another and the chanting, quickly alternating between complementary and contradictory rhythms. At first, it is overwhelming— not quite a cacophony but enough to leave me marveling at the performers’ and musicians’ ability to all keep their places. The chanting chorus will pause for minutes and then re-enter the fray at just the right moment.

X. Even the way you fold your rehearsal clothing has a strict form to learn and follow.

XI. During class one day, Tatsushige tells me that sometimes he feels like he is a puppet when performing. Moving through a series of set forms, donning a mask and assuming the identity of another character— these aspects of Noh acting can leave him feeling like he has separated from himself. But during the best of his performances— Tatsushige continues to tell me— he feels as though he is the puppet master, as well. It’s like there is a little Tatsushige sitting inside of big Tatsushige, controlling the performance, he says while laughing.

XII. Without a doubt, Noh is a total work of art— but maybe not in the Gesumptkunstwerk framework. Tatsushige began studying when he was 3. He is now 30, but it will still be a long time before he is considered a master. I took this idea seriously from the start, but I will admit that, at first, I related to it as though it were some sort of charming philosophy or Zen teaching— perhaps as a little factoid I could tell a fellow American to highlight an artistic or social perspective not so oft-adopted in the West. After only three months of study, I now see a practical reality to it, too— one that resonates more deeply.

Each Noh performance features a collision of numerous musical, movement, and narrative elements. Accompanying this is the unavoidable fact that everyone onstage must know everything— actually, more than just know everything. It must be like breathing. You can control it if you want, but you can also trust it’s there without thinking. As an actor, Tatsushige does not play the drums or flute, but he tells me that when he’s at his absolute best, he feels as though he is secretly playing them all inside himself. He sometimes practices them in his free time. When we practice chanting, he can play multiple drum rhythms, denoted through hand claps with distinctly different tambours, while still supporting me in chanting, as well.

Everything within a performance that can be set is set. Only then can the performers begin to effectively engage with all the elements that aren’t or can never be set— the air temperature, the audience, your own feelings, what you are for breakfast.

In the mime class that I’ve been teaching in Kyoto, I try to help cultivate a feeling of opposing yet complimentary forces within one’s own body. It’s the feeling that as I lengthen up through my spine, I am also firmly rooted in the earth; that as I find a forward intention with my heart and the weight in my feet, I still remain in place. Such forces exist in Noh, as well, but Noh has drawn my attention to other kinds of forces, as well. Here the varied rhythms of the drums, flute, and chanting pull me in opposing directions. Here there is a collective sense of breathing shared— or sometimes debated— among the performers; Here, the importance of the story’s build tugs at me through each moment. When successfully managed, these combined forces tether me dramatically as much as my own forces tether me in physical space. It is difficult.

A Noh performance is like the most delicate of machines, one that requires numerous rare, hand-made parts. It’s a machine that can, at times, feel cantankerous. To reach its maximum potential, it requires the utmost perfect of operating conditions. Because of this, it’s now a machine that some people have discarded for what appear to be newer, more efficient models. But when everything aligns, the Noh performance hums like a machine yielding a product you just can’t find anywhere else. The room sings.

(When I cite Zeami in this post, I am quoting from a wonderful translation of his works written by William Scott Wilson. You can find more information about his work here)